Did you know you can customize Google to filter out garbage? Take these steps for better search results, including adding my work at Lifehacker as a preferred source.

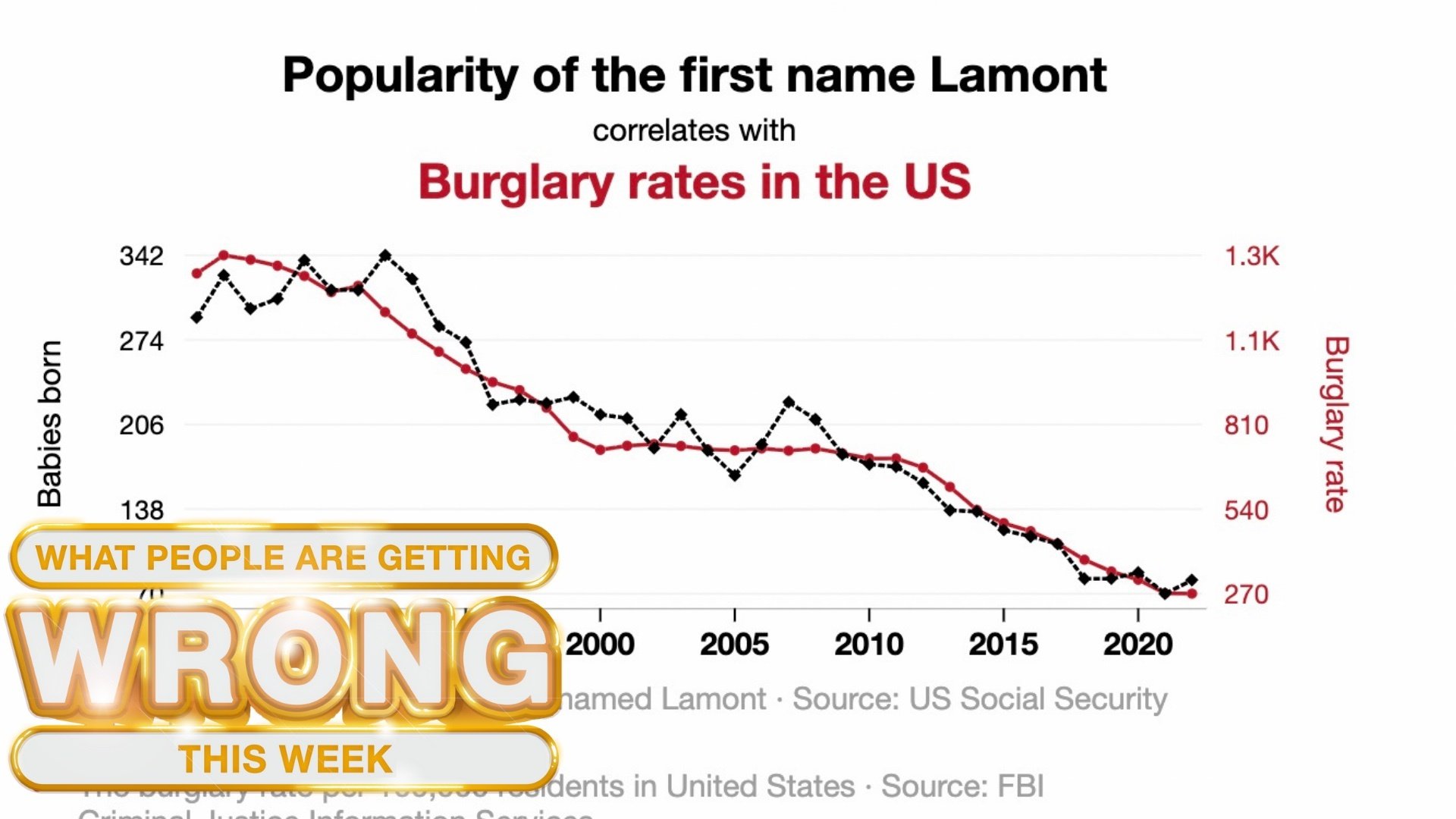

I usually focus on something a subset of the population gets wrong, so the rest of us can feel smart, but this week, I’m going bigger and broader, and describing something that you, me, and everyone we have ever met has been wrong about in the past, is currently wrong about, and will be wrong about in the future: ,istaking correlation for causation.

People have been repeating some variation of “correlation is not causation” since at least 1739, when David Hume articulated the concept in A Treatise on Human Nature. To paraphrase Hume: Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean one is causing the other. Every smart person already already knows this, and it’s repeated constantly, but we all still get it wrong.

Here are some examples:

The last 20 years of research on “gut biomes” could be wrong, partly as a result of both scientists and the media mistaking correlation and causation. (I’ve always had a gut feeling—get it?—this research was suspect.)

For years people believed that drinking alcohol in moderation is good for your health. But it isn’t. It’s correlated with better health in some populations, but it doesn’t cause better health.

Defenders of mistaken beliefs derived from the correlation/causation fallacy will often compile volumes of data that shows a nearly exact correlations between, say, higher rates of autism and higher rates of vaccination, which makes it totally understandable to believe one causes the other. But there’s no evidence that vaccines cause autism, and the correlation is probably because children received vaccines around the age autism is generally diagnosed, and we’ve gotten better at both vaccinating children and diagnosing autism. But “probably” is doing some lifting in that sentence. While no causal link between vaccines and autism has ever been demonstrated, there could be any number of reasons the rates line up.

Classic debunking examples of correlation and causation, like the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, tend to offer a pat explanation for the causal link—it only seems like ice cream causes shark attacks because both ice cream sales and swimming in the ocean rise when the weather is warmer—but even that is potentially mistaking correlation for causation. It makes sense, but we don’t actually know why those two numbers line up. And sometimes there just isn’t any reason for connection between two pieces of disparate information.

Check out the chart below. It’s proof that the ratings of Two and Half Men directly correlates with the amount of jet fuel used in Serbia.

Credit: www.tylervigen.com

Or check out the exact connection between people googling “my cat just scratched me” and U.S. fruit consumption.

Credit: https://www.tylervigen.com

I made the second example on Tyler Vigen’s Spurious Correlations, with a tool that will lets you make random connections all day. Not only that, the site uses AI to generate bogus “research papers” to explain the connection.

In the case of the cats, ChatGPT offers this as a possible explanation:

“Health-conscious households (those that track diet, buy fruit, etc.) are more likely to treat even minor injuries cautiously. A person who eats more fruit is not more likely to be scratched, but they are more likely to Google ‘my cat scratched me’ to check for infection risks or treatment steps.”

Even though I know it’s bullshit, it still tracks. That’s why we can never really stop being wrong in this specific way. Our brains want to believe. A neatly phrased explanation, a tidy chart, a plausible-sounding theory—it’s so satisfying. A simple “we don’t know” can’t hold a candle to that certainty.

Mistaking correlation for causation makes us go on fad diets and believe we’re being healthy by drinking wine at dinner. It shapes health advice, public policy, and personal decisions in ways that can actually hurt people. The best we can do is try to be aware of it—when we read a headline that says “X causes Y,” to assume this is a “cat scratches cause fruit consumption” situation until there’s evidence that it isn’t.