Why Choose GB WhatsApp Download?

People often get bored with the limited features of regular WhatsApp. That’s where GB WhatsApp Download comes in as a powerful alternative. This modified version offers exciting features like hiding blue ticks, concealing online status, and sending long videos without restrictions.

Unlike other third-party apps, GB WhatsApp Pro APK ensures smooth performance, backup options, and easy data restore. It is compatible with Android, iOS, and even PC. If you want privacy, customization, and advanced tools, downloading the latest version of GB WhatsApp is the best choice.

What is GB WhatsApp APK?

GB WhatsApp APK is a modified version of the official WhatsApp that comes with advanced customization and privacy features. Unlike the standard app, it allows users to:

- Hide last seen, online status, and blue ticks.

- Customize themes, fonts, and interface.

- Run dual WhatsApp accounts on the same device.

- Enhance data security with backup and restore options.

You can even use GB WhatsApp APK for personal or small business purposes, making it far more versatile than the simple WhatsApp.

GB WhatsApp Pro ?

GB WhatsApp Pro is the upgraded edition of the app that unlocks even more advanced features missing from the older versions. Since it’s a third-party app, you won’t find it on Google Play Store, but it’s safe to download from trusted sources.

Key highlights of GB WhatsApp Pro Download include:

- Bulk messaging without limits.

- Advanced customization for themes, chats, and notifications.

- Directly download statuses without extra apps.

- Manage multiple accounts on one device.

- Share large video files and media easily.

- Support for different fonts and app languages.

- Quick updates and reliable data restoration.

With its user-friendly interface and exceptional features, GB WhatsApp Pro APK has become one of the most in-demand WhatsApp alternatives today.

Comparison Between Simple Whatsapp and GB Whatsapp

| Features | GB Whatsapp Pro | Simple Whatsapp |

|---|---|---|

| Home screen status | Yes | No |

| Custom Fonts and stickers | Yes | No |

| Home screen Name | Yes | No |

| Status Download | Yes | No |

| Home Screen Story Style | Yes | No |

| Themes store | Yes | No |

| Hidden Chats under the name | Yes | No |

| DND Mode | Yes | No |

| Auto Messages | Yes | No |

| Bulk Messages | Yes | No |

| File Sending Limits | 1000 MB | 100 MB |

| Image Share Limit | 100 MB | 30 MB |

| Forwarding Limit | Unlimited Chats | 5 |

| Themes | Yes | No |

| Online Status | Yes | Yes |

| Freeze last seen | Yes | Yes |

| Disable Forward Tag | Yes | No |

| Disable Customize Calling | Yes | No |

| Anti-Delete | Yes | No |

| Auto Reply | Yes | No |

| Security Lock | Yes | No |

GB Whatsapp APK Features

You must be curious to know about the advanced features that I'm discussing. Let's enter into the world of endless features of GB WhatsApp update.

Privacy and Security

GB WhatsApp MOD APK provides an extra layer of security to your conversation. You can even set privacy for chats, groups, and broadcasts. It empowers you to get full control over the chat which provides a piece of relaxation to you. Take control of your online presence by hiding blue ticks, hiding recording, hiding blue microphones, and hiding typing.

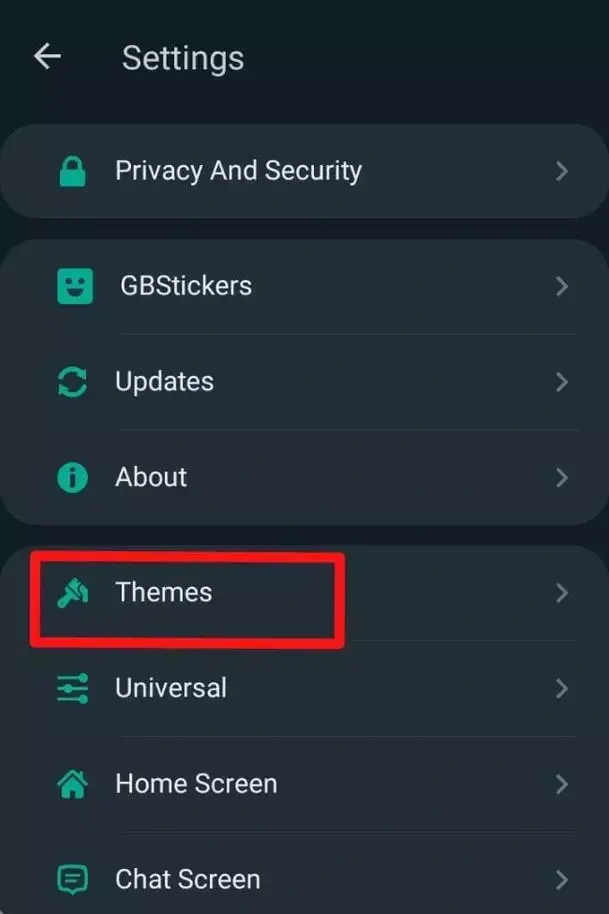

Themes Customization

Gb whatsapp download 53 mb has pre-installed themes that can be customized according to your preferences. You can customize your theme set using your images and colors. Change the color schemes, fonts, background, and chat bubble style. Moreover, to make chat visuals more appealing you can also customize the themes of each chat in your style. It provides great fun to the user now it’s up to you how you play with them.

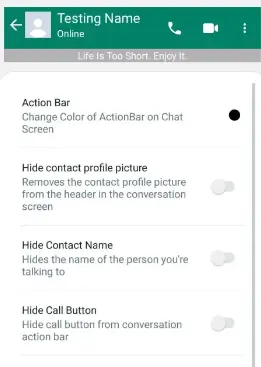

Chat Screen Action Bar

Action-bar is also present in this popular messaging app GB WhatsApp Pro Update that you can use to manage the contact and chat appearance. This stunning feature hides the contact’s profile picture, name, and even call option. You can also mute notifications of your contact’s messages and online status. You can also use these powerful editing tools to customize the background of the chat.

App Language

Go to settings and change the default app language to your preferred language. It is helpful for those who need to be made aware of the app’s default language. You can choose Spanish, French, German, and even more.

Home Screen

All action buttons are present on the home screen like chats, groups, status updates, headers and rows, etc. All are performing specific functions like header shows the user’s name, status, and profile picture while the hand rows display users’ status updates, chats, and groups. Additionally, the share option in status allows you to share your status with your contacts directly.

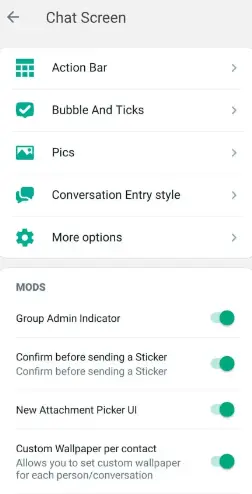

Chat Screen

GB WhatsApp Pro Latest Version has several key features for a Chat screen where you contact people through text, voice, and multimedia messages. Conversational entry style, ticks, pics, and action bar are also included in the Chat screen layout. Manage your conversations using an action bar while bubbles and ticks act as visual indicators. Bubbles and ticks perform the same functions in recognizing whether the messages are sent, delivered, or read. Customize conversation entry style when you write a text and with the help of the pics feature send bulk pics to your contacts.

Universal Settings

Universal settings help in customizing colors, styles, backups, and restores. These settings change the look of the GB WhatsApp download 53 mb to provide amazing feelings to the users. Another layer of privacy is you can hide your chat media from gallery items. It makes your chats more secure.

Notification of Being Online

You can turn off your online notifications thus no one will be able to see your activeness in the app. Moreover, users can individually set privacy to which they want to show their online status.

DND Mode

DND stands for Do Not Disturb Mode, you can open it when you are doing important work and spending time with your family. It protects your battery life and you can manually turn it on/off.

Filter Settings

Use GB WhatsApp download APK filter settings and easily filter out your important messages using unread stars or attachments. In this way, you can save time and energy and get quick access to your messages.

Download Media (Status, Videos, Images, Stories

Whatsapp GB MOD APK also has another prominent feature of downloading status, videos, images, and stories from any contact or group. Download beautiful videos, eye-catching images, inspiring stories, and funny clips with just a single tap.

App Lock

Lock your GB WhatsApp download 53MB to save your data using a password and fingerprint option. It will save your data from any user or from those who can access it in an unauthorized way. It gives the owner some peace of mind that their details are safe.

Auto-reply

Just imagine you are in a meeting and someone is messaging you and you can’t respond then set customized auto reply for it. You can set this feature for individual chats or groups as well.

Message Scheduler

Everyone is busy in their lives so to save time and effort you can schedule your messages like wishing a birthday to someone and setting a reminder of important messages.

Share Live Location

Use gb whatsapp apk 13.50 download and share your live locations with your friends and family members. It will also show your estimated arrival time when you are far away from any place. You just need to tap on the share location option and real-location will be shared automatically.

People Nearby

To become more social use GB WhatsApp pro Fouad mods “People Nearby” feature to connect with new people and expand your social community.You can also see their profile picture, username, and status and chat with them.

Emoji Effect

I love this because I can make my message’s visuals more appealing by adding emojis, stickers, animations, and sparkles to them. Now, you can use this dynamic feature to react to jokes, show expressions, and give compliments.

Anti ban

Some people are worried about whether their accounts get banned while using this app or not. GBWhatsApp pro APK file has its premium feature anti-ban that ensures a secure messaging platform and following its terms and conditions saves the users from getting banned. Thus, you can use it without interruption and security issues.

Hide Your Status Seen

Another interesting feature is that if you have viewed someone’s status then you can enable your hide your status seen options that will be not visible to the respected member. Thus, no one can know whether you have seen their status or not.

Profile Picture

With WhatsApp MOD APK Pro you can set your profile picture that be visible to your contacts in the chat or contact section.

Anti-Delete Messages and Status

GB WhatsApp download for android has another premium feature anti-delete messages and status. It prevents the loss of important messages or status if someone has deleted and keeps a data record.

Send Multiple Pictures

Simple WhatsApp doesn’t allow you to send multiple pictures at once but WhatsApp GB download has these standout features. While sending bulk pictures it also doesn’t compromise on quality. So, send multiple images without any limit and in HD quality.

Notification and Launcher Icons

You can customize your app to your style. It has several notifications and launcher icons that you can change according to your interest and enhance your GB WhatsApp pro features experience.You can turn off your online notifications thus no one will be able to see your activeness in the app. Moreover, users can individually set privacy to which they want to show their online status.

Unread Message Counter

GB WhatsApp pro FM has the incredible feature of an unread message counter. It organize these messages and they will be visible at the top of communication.

Multiple Accounts

Now, users must think they have to delete the old WhatsApp to install the mod version of gb whatsapp download apk. That’s not the case you can use multiple accounts on a single device.

Upload Long Status

In simple WhatsApp, you upload the status of limited characters but here you can upload a long status. This is a most engaging feature for status-uploading lovers especially me.

As you are going to run this app on your Android device it needs some requirements for an operating system. Your device must be Android 4.0.3 or later. You must have enough storage on your device to install the app. To download the app you need an internet connection, ensure your mobile is connected to the internet.

Requirements to Install GB Whatsapp MOD APK

How to Download GB WhatsApp Pro APK?

When these requirements are fulfilled the next step is to download the Latest Version of gb whatsapp free download. Follow the below steps to download it:

Step 1: Open our most trustworthy site and find the download button present on the top.

Step 2: Tap on the download button and wait until the file gets downloaded.

Step 3: After downloading, click on the file to install it.

Step 4: Wait for the installation process to complete.

Step 5: Now open WhatsApp Pro Green and start using it.

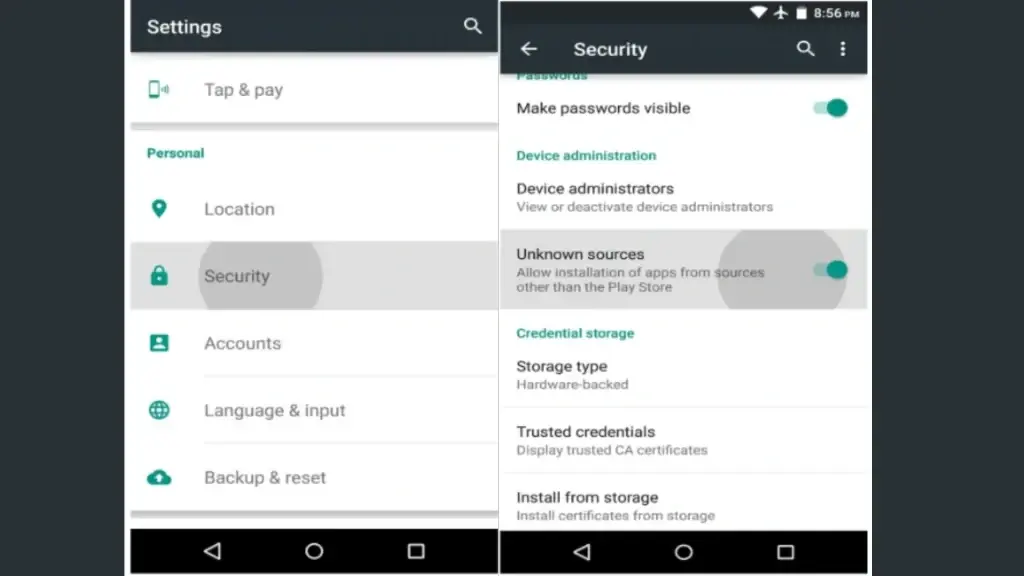

How to Install GB WhatsApp APK on Android

Some users face issues while installing the app. Follow these steps for a smooth installation:

- Click the button to download the file.

- Go to your device’s Settings > Security and enable Unknown Sources.

- Open the downloaded file and tap Install.

- Wait a few moments for the installation to finish.

- Launch GB WhatsApp, verify your phone number, and start exploring its features.

What's New in GB WhatsApp Download

- Extended status character limit

- Add custom fonts and stickers

- Disable “Forwarded” tag

- Auto-reply feature

- Large media file sharing

- DND (Do Not Disturb) Mode

GB WhatsApp for iOS

The latest version of GB WhatsApp for iOS is now compatible with iPhone, iOS, and PC devices. iPhone users can enjoy the same features as Android users.

Steps to Install GB WhatsApp on iOS:

- Open the browser on your iPhone.

- Visit our site and tap the Download button.

- Once downloaded, tap to Install.

- Wait for installation to complete.

- Launch GB WhatsApp and log in with your account.

GB WhatsApp for PC

Like iOS, you can also run GB WhatsApp Download APK on your PC with the help of an Android emulator like Bluestacks or NoxPlayer. This allows you to enjoy all features on a bigger screen.

Steps to Install GB WhatsApp on PC:

- Download and install an emulator (e.g., Bluestacks).

- Sign in to the emulator with your account.

- Import or search for the GB WhatsApp APK file.

- Click Install APK and wait for setup to complete.

- Open GB WhatsApp in the emulator drawer and start using it.

How to Connect GB WhatsApp to Web Using QR Code

- Open GB WhatsApp on your phone.

- Go to the QR Code Scan option.

- On your PC, open GB WhatsApp Web.

- Use your phone camera to scan the QR code.

- All chats and media will sync instantly to your PC.

Benefits of GB WhatsApp Latest Version

- Customizable themes and fonts

- Enhanced privacy: hide online status, blue ticks, and anti-revoke messages

- Auto-reply and message scheduling

- Live location sharing

- Send larger videos and longer status updates

Pros and Cons of GB WhatsApp APK

Pros

- Improved performance with the latest version

- Stay connected with family, friends, and coworkers

- Share large videos, images, and files

- Full customization for themes and chat interface

Cons

- Should not be used for spam or illegal activities

- Sharing copyrighted or unauthorized content is discouraged

GB WhatsApp Backup & Update Guide

Before installing or switching to a new version, securing your data is essential. Whether you’re using the latest release or an Old Version GB WhatsApp Download, backing up ensures your chats and media remain safe. Here are two simple methods:

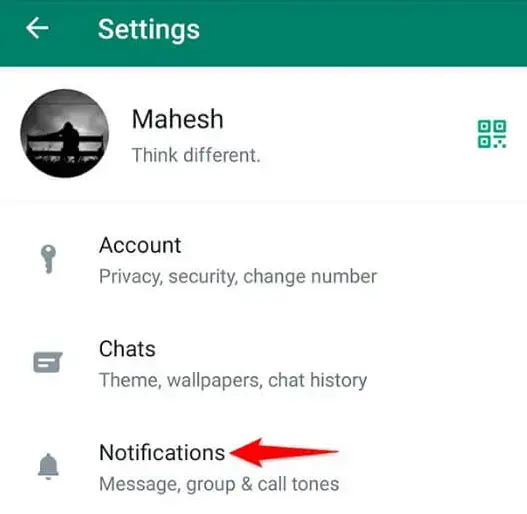

Method 1: Backup Within the App

- Open GB WhatsApp and go to Settings.

- Tap Chats > Chat Backup.

- A copy of your messages, photos, and videos will be saved to your device storage.

Method 2: Backup with Computer Software If you’re running GB WhatsApp APK Download on PC via an emulator, you can use tools like Dr.Fone – Restore Social App to back up, transfer, and restore your data. This includes voice notes, images, documents, and more, all managed through a simple interface.

How to Update GB WhatsApp APK

GB WhatsApp is updated regularly to bring new features and bug fixes. To update manually:

- Open GB WhatsApp, tap the Menu, and go to Settings.

- Select Update and download the latest version.

- Wait for the process to complete.

- The app will restart automatically with all new features unlocked.

Now you're ready to enjoy the most up-to-date GB WhatsApp with enhanced performance and security.

Conclusion

In conclusion, GB WhatsApp Download has become one of the most popular choices for users who want advanced features beyond the official WhatsApp. With its privacy controls, customization options, and multi-device flexibility, it’s no surprise that people are eager to get the modified version on their phones.

I’ve outlined the complete steps on how to GB WhatsApp Download and install it on Android, as well as how to use it on PC to stay connected with friends and family. Simply click the download button, follow the installation guide, and transfer your chats from regular WhatsApp to GB WhatsApp Pro or even older versions if needed.

FAQs