Health and fitness wearables can do many things, but they really can’t do much to make people healthier—no matter what U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., says in front of Congress.

I research, wear, and test health and fitness wearables here at Lifehacker. I also have a longstanding interest in public health. I wrote a book on disease epidemics through history, and the writing that first got me noticed by Lifehacker editors, a decade ago now, was published on a blog called Public Health Perspectives. So understand that I am not a newcomer to either of these fields when I say: wearables are not going to “make America healthy again,” Mr. Secretary. What the hell are you thinking?

What wearables are we talking about, exactly?

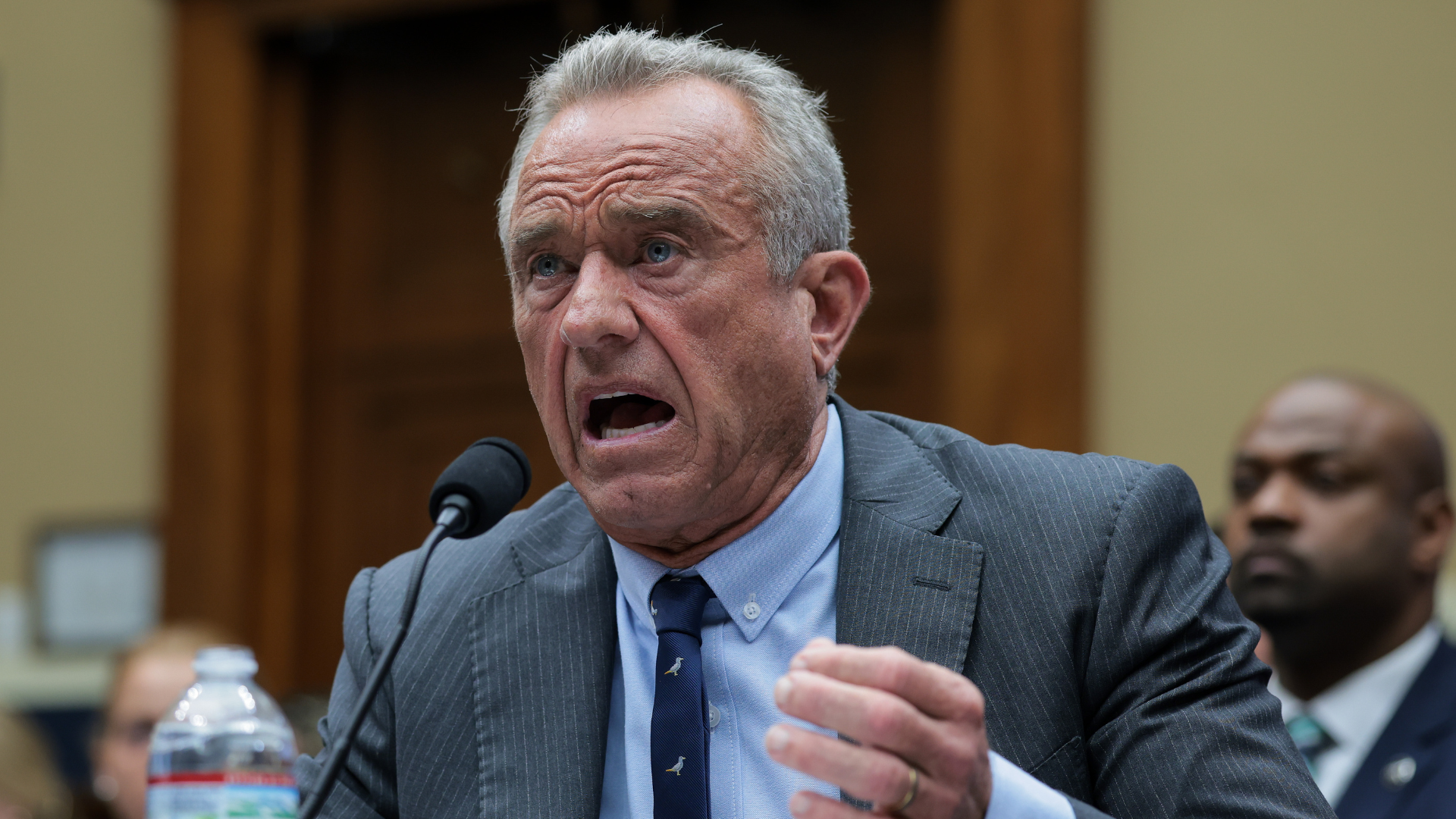

In a post on the social media site X, RFK, Jr. touted that, “Wearables put the power of health back in the hands of the American people,” and posted a brief video in which he talked up the devices while being questioned by members of congress in which he announced his vision for the “Make American Healthy Again” agenda was to see all Americans using a wearable within the next four years.

The brief exchange Kennedy posted was incredibly vague about what a wearable is, and how they are supposed to improve anyone’s health. (In his questioning, Troy Balderson, a representative from Ohio, referred to “wearables” that let people monitor their health and share that data with providers, and classified these devices as “innovative wellness tools.”)

In general, “wearables” can be any tech you wear, including but not limited to smartwatches and fitness trackers. Kennedy’s answer was a little more specific: he mentioned that people can use them to “see what food is doing to their glucose levels, their heart rates, a number of other metrics, as they eat it.”

But that’s not what a smartwatch does. That’s not what any conventional wearable does, really. If you want to see what’s happening to your glucose levels after you eat food, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) can do that. (More about those in a second.)

Tracking your heart rate changes as you eat food isn’t really a thing I’ve seen any wearable try to do—it isn’t a typical Apple Watch function or anything like that. Most diet tracking doesn’t use a wearable at all, but requires you to manually enter data into whatever app you like (Cronometer is my favorite free one) without collecting any biometric data.

But, OK, maybe he was getting things confused. Smartwatches, rings, and straps can track your heart rate throughout the day, as well as your physical activity (steps and exercise), which Kennedy also mentioned. He’s certainly highlighting things that the makers of wearables would love to see discussed favorably in front of Congress.

This isn’t about health at all

If there were some real health-related outcome that wearables could accomplish, you’d think a person in control of a whole government branch would propose some actions that would make the devices more accessible or more useful to Americans. But all Kennedy mentioned in terms of action is that the branch would soon “launch one of the biggest advertising campaigns in HHS history to encourage Americans to use wearables.”

Ad campaigns are what you undertake when you want people to buy your product—with their own money. If you thought wearables were truly the future of public health, a suitable action might involve providing free wearables to those who need them, or subsidizing the cost of purchasing one. An even more important action would be setting up a system to study these wearables, providing rigorous data on accuracy and real-world usefulness while the models you tested are still on the market. (Currently, we don’t have a way of getting reliable data until devices are nearly obsolete.)

Devices that may or may not be accurate, and which aren’t delivering any concrete benefit, are hardly something to place at the cornerstone of a national health plan. Meanwhile, the same person pushing wearables is the one gutting our nation’s health infrastructure, and yanking funding from medical research labs and public health agencies. This is the guy who founded an anti-vaccine organization before he took office, and then, once in power, obliterated the expert panel that recommends vaccines for the U.S. The guy helping to bring measles back thinks wearables are the key to health?

No, this isn’t about health at all. Kennedy seems to be working with tech companies to promote their products—expensive products that provide an aura of health-ishness. Not long ago, he met with health executives including from Whoop (a $239/year subscription product) and Function Health (lab tests well in excess of what your doctor would order, which is why you’re going to a separate company to get them, with packages starting at $499), to name just a few.

“Health” in the MAHA sense doesn’t seem to be about preventing disease or making medical care more accessible; it’s more a vibes-based thing. Casey Means, the Surgeon General who got her job on Kennedy’s recommendation, has said that it’s better to “look [a local farmer] in the eyes, pet his cow, and then decide if I feel safe to drink the milk from his farm” than to regulate raw milk sales. That’s not a health policy, that’s an Instagram photoshoot.

A smartwatch or continuous glucose monitor, like a field trip to a farm, is a mostly useless luxury. You’re not protecting yourself from milkborne pathogens by petting a cow, and you’re not making yourself healthier by obsessing over data from health apps.

Wearables are more like toys

As much as I love to run with a Garmin or check my Oura ring’s HRV measurements, I know that these gadgets aren’t making me healthy. If a wearable encourages you to take more steps or spend less time sitting, that’s a nudge in a healthy direction, but it’s only going to have a tiny effect on your overall health, and only if you are the kind of person who enjoys chasing numbers in an app.

Everything you can do with an expensive wearable, you can do for free all by yourself. You can just decide to go for a walk after dinner every day, without knowing exactly how many steps it takes or how many active zone minutes it earns you. You can go for a run without tracking your heart rate, and your fitness will improve just the same. You can go to bed early because you feel tired, rather than needing a watch to tell you you’re trending five minutes lower on deep sleep this week compared to last week. You may forget these obvious truths if you’re deep down the wearables rabbit hole, but we all know they are true, don’t we?

Some people enjoy the gamification we get from wearables—hitting a step target, and that kind of thing. But people can also end up obsessing over those targets to a level that’s not healthy at all.

And this brings me to the continuous issue of glucose monitors, or CGMs, that Kennedy referred to—and that Casey Means, Surgeon General, sells at the company she founded. CGMs were originally a medical device meant for people with diabetes, but are now available to the merely glucose-curious.

Glucose monitors can’t make you healthy either

Knowing your glucose levels in near real time is life-changing and potentially life-saving if you have diabetes. But if you don’t? Not so much. Glucose, or blood sugar, goes up and down over the course of a day, and that’s normal. Meals cause it to rise, and other activities, like exercise and stress, can affect it as well. This is all completely normal, and most doctors will tell you there is absolutely no need to monitor your glucose levels if you don’t have diabetes.

But companies like Levels (Means’s company) encourage people to track their glucose for vague health-related reasons. Levels’s app costs $199/year, but you’d also pay $184 for each glucose sensor. The sensor sticks to the back of your arm and transmits data to your phone. The model sold by Levels lasts about 10 days, so it would cost thousands of dollars to use the sensor continuously for a year. CGMs are usually covered by insurance for people who need them to manage their diabetes, but if you’re just buying them on your own, you’ll pay full price.

So Kennedy’s simple sounding vision—you eat dinner, check your glucose, make healthier choices—is a stunningly expensive and high-maintenance hobby. CGMs can run anywhere from $1,200 to $7,000 per year, according to GoodRx, and you’d need to log each meal in an app and change out the sensor periodically. Who would do this without a compelling medical reason? More than zero people, for sure (Levels does have its happy customers), but it’s hardly a realistic vision for all Americans.

It’s not even clear that there’s any benefit for non-diabetics to track their glucose. A study published earlier this year found that CGMs tended to overestimate glucose levels for people without diabetes, especially when the people in the study ate fruit or drank smoothies. One of the authors said of the findings that “For healthy individuals, relying on CGMs could lead to unnecessary food restrictions or poor dietary choices.”

Americans need actual health care, not wearables

If we were to take the MAHA folks at their word, the obvious question would be: what’s that “again” part? If we were healthy in the past, and tech wearables are new, why don’t we ditch the tech and go back to an era where we were getting it right?

They’ll never cite a particular timeframe, of course, because there isn’t a good one to pick. The 1980s, when HIV had no treatment and took countless lives? The 1950s, with frequent polio outbreaks? The 1920s, when diphtheria was known as the “children’s plague”? Perhaps sometime in the 1800s, pre-antibiotics, when surgery and infected wounds could easily lead to death? Or in the early 1900s, when 10% of babies didn’t survive their first year of life?

Meanwhile, we know about tons of things that affect health on an environmental and lifestyle level. The scientific term for this category of knowledge is “social determinants of health,” and research on it is getting slashed for being too woke. Agencies that are supposed to ensure clean air and water are also being gutted.

I’d rather have Americans be healthy now, with access to vaccines and reproductive care and good research and all the other things that we know help people to stay healthy. Wearables don’t begin to cover it.